From Dadaists to Synthetic Media: the production of presence and how it has changed in 100 years

What Marcel Duchamp, contemporary memes, neural networks, and Hans Gumbrecht all have in common

From the very beginning of their existence, people have left material or intellectual imprints on their surrounding environment. Just look at ancient cave drawings or modern scrawls on famous historical monuments that say "I was here." What are these if not the embodiment of the human desire to leave our mark now, for the future?

Whether because of egoism and narcissism, the ancient fear of the infinitude of the world, or the brevity of life and our vulnerability in this world, we are always trying to continue and sustain ourselves in reality. From a biological point of view, this is called self-replication — making copies of ourselves or our parts for the sake of our continued existence. The desire for self-replication is also typical of viruses, but they lack the key motivational component that drives people — feelings and emotions.

While the human desire to carve ourselves into space and the moment remains, the tools and ways we do it have changed. First, it was rock art, architecture, books, photos, and other analog media. Today, we create the same "memorials" to ourselves but have transferred them into the digital world. Social media profiles, avatars, memes, filters, photo editors, and NFTs all make it possible to create a digital memorial to oneself and create one's presence in it.

The current zeitgeist has changed how we interpret creative work: the culture of semantics is being replaced by the culture of asemantics. The literal meanings of signs and symbols have been replaced by the experience of existence in the moment of aesthetic interaction with a work of art. And these feelings, regardless of their primary symbolism, have significant value.

This is not new

To explain the connection between our desire to carve ourselves into our environment and the opportunities of the digital world, let's turn to the Dadaists and their idea that the senses are not what they seem. Hello, David Lynch and Twin Peaks with the now-iconic "the owls are not what they seem."

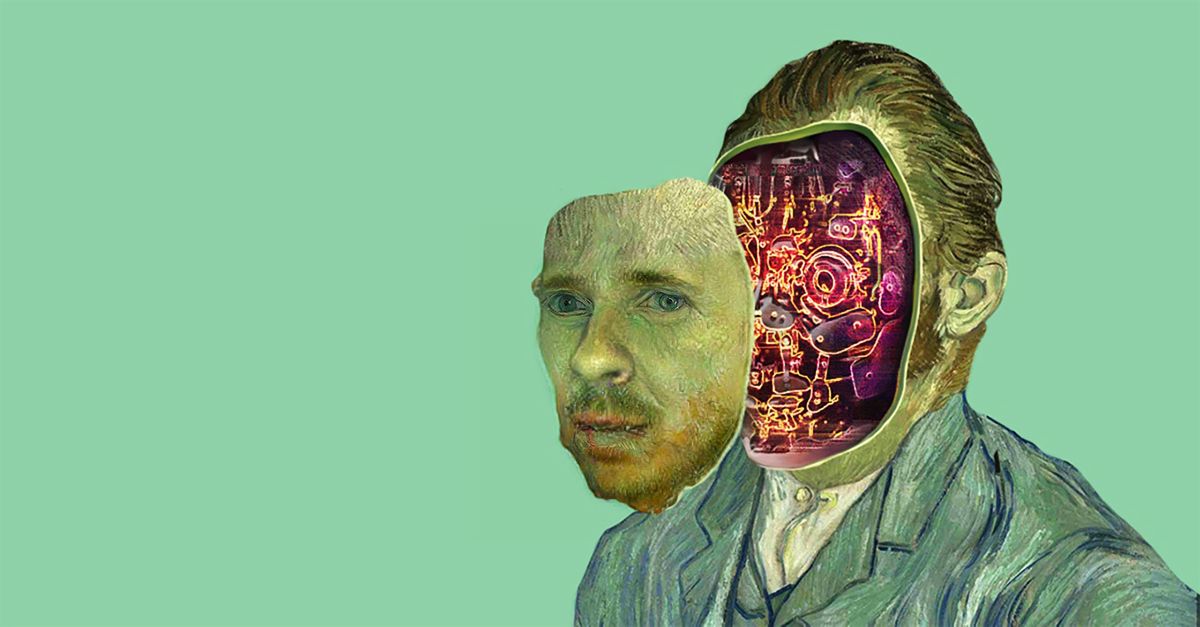

In 1916, Marcel Duchamp took a urinal from a man's bathroom and called it art. In other words, he took its old semantic sign and gave it a new meaning. The Dadaistic art method of “readymades" shocked the public at the time and was based on the simple idea that anything can be art. A work can become art at the author's designation, and in the context of an exhibition or museum.

Indeed, why is Da Vinci's Mona Lisa considered art, but Duchamp’s reproduction of the Mona Lisa with a mustache (entitled “L.H.O.O.Q.”) is not? Rather than debating the true definition of artistic creation, it is easier to accept that we live in the post-“aura of art" times. The author of this term is Walter Benjamin, who wrote the novel "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" (1936) just 20 years after Marcel Duchamp's urinal.

Benjamin was concerned that original works of art were being copied and duplicated, and would lose their original meaning. This idea continues to this day, and I wonder what Benjamin would say about today’s NFTs. In fact, all previously created artworks become an element or filter of new artwork. And the way of assembling these elements is a new kind of creativity.

The Mona Lisa, Polaroid photos, religious icons, cinematography, advertising — anything can be art, as long as a creator presents it as art. Its form does not matter – what matters is the emotional intensity the viewer experiences and the author's presence, position, character, and message.

And what about today?

Today the desire for self-replication and the number of technological tools available allow anyone to create new forms of content quickly and easily.

Nowadays, if someone wants to create the Mona Lisa with different hair, they don’t have to repaint it and start a whole new art trend as the Dadaists did. They just need to use a few simple tools that allow them to modify and publish the content (Reface, Snapchat, Wombo). The new Mona Lisa can have a mustache, become Asian, and start moving and singing like Nicki Minaj.

This is still creativity, but written in a new technological language. And this creativity has a low entry threshold, which means that it is accessible to almost everyone. This creativity also has a sociocultural function since the authors of such art can be not just one person but many, and each can add something of their own to this work.

This trend can be seen in memes and meme generators, such as the website that inserts Bernie Sanders into any photo from Google Maps, a tool to take selfies on Mars with the Perseverance rover, and the endless stream of creativity with the Homunculus loxodontus (“The One Who Waits”) sculpture.

Claim your presence by personalizing content

The idea of the production of presence through the creation or viewing of artwork belongs to the contemporary German-American philosopher Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht. In his book “Production of Presence” (2003), he argues that an aesthetic experience cannot be reduced solely to its semantic meaning or iconic interpretation.

Gumbrecht believes that there is one more component of perception apart from the semantic interpretation of a work of art — the asemantic one. This is the material, sensitive, emotional, and even physical experience of presence that people feel when interacting with art. This very aspect is essential and underestimated. The effect of presence is significant in Gumbrecht's aesthetic experience.

Thus, the production of presence is a cultural mechanism that generates thoughts and presence, that is, people's experience of the current moment, of being in the “here and now.” In other words, it means feeling the tangibility of intuitive music or one's involvement in the visual creation of art. We might later forget the artwork itself, but we will not forget the emotion we felt when interacting with it. This interaction with art is a way of personalizing it and placing it in our personal context. Gumbrecht even describes a sense of something mystical and divine that spurs people to produce a presence.

Aren't people's actions for their self-replication in the digital space the pure production of their presence? Content creation, personalization, evaluation, interacting with content, and reacting to it are all parts of an aesthetic experience that allows people to manifest themselves, to become alive, to experience the “here and now” in their environment.

- Drawing a mustache on the Mona Lisa is a way to show a personal connection with the phenomenon of the Mona Lisa; a way to say to others, "Here I Am."

- Inserting that picture of Bernie Sanders into different places and situations means giving a new dimension to the discussed phenomenon; it's like telling everyone, "Here is my version of events."

- Posting your selfies on Mars means feeling something about this day, this year, this moment; it's like telling the world, "I am here, I am alive."

In all of these cases, the production of meaning plays a much smaller role than the production of presence. When creating this type of content, authors are more interested in making a statement about themselves than delivering a specific message. But once the author has finished their work and given their content to the audience, the absolute creator is the one who interacts with this content: both directly (by completing it, taking pictures of it, applying filters or adding text), and by living the experience of watching or listening to it.

Creating emotions through the production of presence

Gumbrecht's aesthetics and the Dadaists' approach to the senses in art explain the popularity and virality of new media tools and technologies that have emerged over the past few years. TikTok videos, instamasks, the development of neural networks, deepfakes, and synthetic media are the technological tools of today that allow people to establish their presence in the digital world quickly and easily.

For the market of technological products, the production of presence is a way to analyze a new kind of data – product+anthropological metrics based on human emotions.

In the context of product language, the production of presence is a mechanism for keeping people's attention, the bait that encourages people to interact with this type of content for as long as possible, to personalize it, and to share it with others. It is an eternal engine for new meanings, because adding something of your own can be done in a circle.

The amount of information that exists today and the level of technological development that science has given us have brought us to an unprecedented time in human history. We have a chance to recontextualize all of the content we know, provide it with new meaning, and launch a tireless mechanism for producing presence using neural networks and synthetic media.

This idea is based on the human desire to carve ourselves into our environment and is accompanied by a strong emotional anchor to everything that is "mine," "bears my mark," or is "created by me." And this has become technically feasible in large part due to neural networks and the range of possibilities of working with content that they give us today.